I hesitated whether to share Die Löwenbraut or not, because its duration goes far beyond the usual two or four minutes; it even goes beyond the six minutes of The Swimmer, last week's song. However, I think this song is interesting and I hope I will be able to encourage you to take a pause and listen to it.

Die Löwenbraut is part of Drei Gesänge, op. 31, that includes a song we listened some time ago, Die Kartenlegerin. Robert Schumann composed it in July 1840, just after finishing Frauenliebe und -leben; the two works share the poet, Adalbert von Chamisso, who also translated into German the next songs he composed, with poems by Hans Christian Andersen. Let's say that Schumann was at the time in a "Chamisso period"

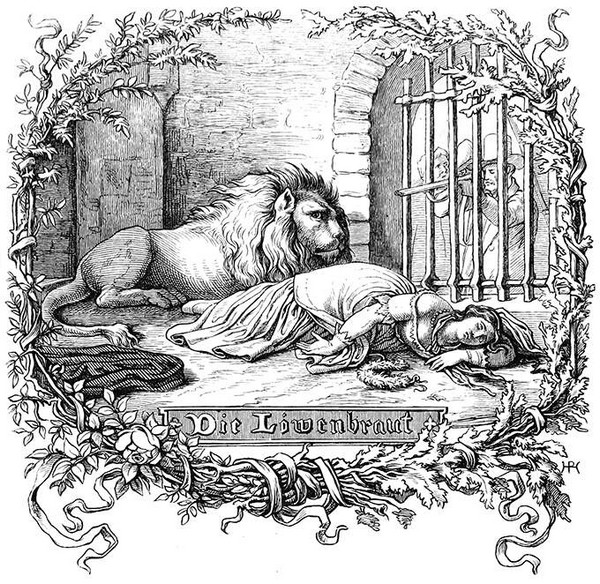

The story of Die Löwenbraut (The bride of the lion) is peculiar: a bride enters a lion's cage and caresses him while remembers sadly the years they passed together. They are adults now, and she will marry and leave, this very day; the meeting is therefore a farewell. The bride kisses the lion for the last time. Then he sees the groom waiting for her outside, and prevents her from leaving by blocking the door; as the groom asks for a weapon, the bride tries to open the door of the cage and the lion swipes at her with his claws. And he lies down by her dead body, waiting for the bullet that will kill him. I can't but feeling that the narrator, one of the two voices that we hear in the long poem of twelve stanzas, empathizes more with the lion than with the bride.

As you can imagine, this Schumann's lied is analyzed, as any other written in 1840, in relation to the situation of the composer and his fiancée Clara Wieck, separated and trying to get marry despite the opposition of Friedrich Wieck, his father (if you want to know more about this story, please follow this link); I wonder whether Schumann really projected his experience on Die Löwenbraut, it seems excessive to me. If so, who would be Schumann? The lion who doesn't accept his fiancée to marry another, a situation more than likely if Herr Wieck overcame his daughter? Or would the lion be Wieck himself, who would kill Clara before he consented to marry Robert?

I was really curious about how Chamisso had come to write that ballad, and I found that he based on a legend that, as usual, should have a little part of truth and much of fiction. I'll try to explain it shortly:

In the middle of the 16th century, the emperor Maximilian II built a pleasure palace in the same place where the luxurious tend of Suleiman the Magnificent had been during the siege in Vienna several decades before (the place is known as Schloss Neugebäude and, if you wish, you can rent it for a wedding). The palace had, among other entertainments, a place where many exotic animals live. In 1590, a great party was held to celebrate the 4th anniversary of the youngster daughter of Emperor Rudolf II; the little girl had just received a present from Bertha, the also four years old daughter of the palace administrator, when a infuriated lion broke into the room; the noise of the loud party had upset it and made it escape from its cage. The armed men hurried to kill him, but, amazingly, Bertha rushed to the lion, embraced it and begged the men not to kill it, Then she took the animal by its mane and gently guided it to its cage. The emperor, shocked by the scene, said that Berta would be called "bride of the lion" from here on out. Chamisso tells with accuracy the rest of the story, his only add-on is the girl's rejection to her marriage.

The ballad is not Schumann's most successful one; it lacks, for example, the power of Belsatzar, but any work from the composer's pen is worth hearing. Besides, as you can imagine, I chose a great performance of Die Löwenbraut; I hope that if I failed, Gerald Finley and Julius Drake will convince you to move, for a few minutes, to a world of legend in which lions fall in love with girls.

Mit der Myrte geschmückt und dem Brautgeschmeid,

Des Wärters Tochter, die rosige Maid

Tritt ein in den Zwinger des Löwen; er liegt

Der Herrin zu Füssen, vor der er sich schmiegt.

Der Gewaltige, wild und unbändig zuvor,

Schaut fromm und verständig zur Herrin empor;

Die Jungfrau, zart und wonnereich,

Liebstreichelt ihn sanft und weinet zugleich:

‘Wie waren in Tagen, die nicht mehr sind,

Gar treue Gespielen, wie Kind und Kind,

Und hatten uns lieb und hatten uns gern;

Die Tage der Kindheit, sie liegen uns fern.

‘Du schütteltest machtvoll, eh’ wir’s geglaubt,

Dein mähnenumwogtes königlich Haupt;

Ich wuchs heran, du siehst es: ich bin

Das Kind nicht mehr mit kindischem Sinn.

‘O wär ich das Kind noch und bliebe bei dir,

Mein starkes, getreues, mein redliches Tier;

Ich aber muss folgen, sie taten mir’s an,

Hinaus in die Fremde dem fremden Mann.

‘Es fiel ihm ein, dass schön ich sei,

Ich wurde gefreit, es ist nun vorbei:

Der Kranz im Haar, mein guter Gesell,

Und vor Tränen nicht die Blicke mehr hell.

‘Verstehst du mich ganz? Schaust grimmig dazu,

Ich bin ja gefasst, sei ruhig auch du;

Dort seh’ ich ihn kommen, dem folgen ich muss,

So geb’ ich denn, Freund, dir den letzten Kuss!’

Und wie ihn die Lippe des Mädchens berührt,

Da hat man den Zwinger erzittern gespürt,

Und wie er am Zwinger den Jüngling erschaut,

Erfasst Entsetzen die bangende Braut.

Er stellt an die Tür sich des Zwingers zur Wacht,

Er schwinget den Schweif, er brüllet mit Macht;

Sie flehend, gebietend und drohend begehrt

Hinaus; er im Zorn den Ausgang wehrt.

Und draussen erhebt sich verworren Geschrei.

Der Jüngling ruft: ‘Bringt Waffen herbei;

Ich schiess’ ihn nieder, ich treff’ ihn gut!’

Aufbrüllt der Gereizte schäumend vor Wut.

Die Unselige wagt’s sich der Türe zu nahn,

Da fällt er verwandelt die Herrin an:

Die schöne Gestalt, ein grässlicher Raub,

Liegt blutig zerrissen entstellt in dem Staub.

Und wie er vergossen das teure Blut,

Er legt sich zur Leiche mit finsterem Mut,

Er liegt so versunken in Trauer und Schmerz,

Bis tödlich die Kugel ihn trifft in das Herz.

Adorned with myrtle and a bridal gown,

the watchman's daughter, the rosy maid,

Steps into the cage of the lion; he lies down

at his mistress's feet, and nestles there.

The powerful creature, wild and unbridled,

gazes devotedly and intelligently up at his mistress;

the young woman, gentle and lovely,

caresses him tenderly and weeps all the while:

"We were, in days that are no longer,

such true playmates, as a child will be with another child,

and we loved and liked each other well;

the days of childhood lie so distant!

Powerfully, before we could believe it,

you were shaking your head with a kingly mane;

I grew up as well, as you can see: I am

no longer a child with a child's mind.

O were I a child again, and could stay with you,

my strong, faithful, honest animal!

But I must follow my destiny

to go to foreign lands with a foreign husband.

He thought I was fair

and I was wooed; it is now in the past:

a wreath in my hair, my good friend,

and so many tears that I can not see.

Do you understand me? You look at me so grimly.

I am already bound, so be calm;

Look, I see him coming, he whom I must follow;

I'll give you then, my friend, one final kiss."

And as the lips of the maiden touched him,

one could feel the cage trembling,

and as he looked out at the young man,

the anxious bride was seized by horror.

He placed himself at the door of the cage, guarding it;

he waved his tail, and roared with power.

She asked pleadingly, threatened and then demanded

to be let out, but he defended the exit with fury.

Outside there arose a confused outcry.

The young man called: bring me a gun;

I'll shoot him down, I'll take care of him.

The beast roared, foaming with rage.

The wretched girl risked moving near the door,

and, transformed, he fell on his mistress:

the lovely form, a grisly crime,

lay torn and bleeding, disfigured in the dust.

And having spilled this beloved blood,

he lay down beside the corpse with a gloomy air;

he lay thus, sunk in mourning and pain

until the fatal bullet pierced his heart.

(translation by Emily Ezust)

The Kin...

The Kin...

Comments powered by CComment