"Mental note: find out more about August von Platen". Platen is the poet of just two lieder by Schubert and five by Brahms, they are such tormented verses that every time I listened to some, I was wondering what could have led the poet to write them. We've known one of the Schubert's lieder, Die Liebe hat gelogen, D. 751 (Love has lied); the other one is Du liebst mich nicht, D. 756 (You don't love me). Those of Brahms’ have similar topics: deceptions, pleas, I know you used to love me, why are you doing this to me... you get the idea, don't you?

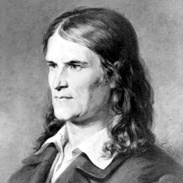

"Mental note: find out more about August von Platen". August von Platen is the poet of just two lieder by Schubert and five by Brahms, they are such tormented verses that every time I listened to some, I was wondering what could have led the poet to write them. We've known one of the Schubert's lieder, Die Liebe hat gelogen, D. 751 (Love has lied); the other one is Du liebst mich nicht, D. 756 (You don't love me). Those of Brahms’ have similar topics: deceptions, pleas, I know you used to love me, why are you doing this to me... you get the idea, don't you?

I didn't take my mental note into practice until the book Brahms and his poets arrived at home some weeks ago; as the title suggests, it studies Brahms' Lieder grouped by poets, a point of view away from the more common chronological order. Among those poets, Platen was mentioned, of course, and besides, just by chance, my earworm at that moment was one of Brahms and Platen's Lieder (which we're listening today). That was a sign, so I carried out my brief research on the poet. The summary, in three words, would be: poor little Platen!

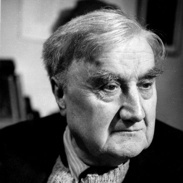

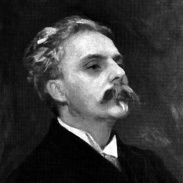

August von Platen was born in 1796 in Bavaria, the son of a noble and impoverished family. He had an excellent education at an elite military school and, despite his delicate health, he enlisted in the army. Once the Napoleonic wars were over, he was granted to go to university and he didn't go back. He devoted himself to the study of literature, especially interested in Persian poetry due to Goethe and Rückert's research and publications; Although his poetry was well considered by many of his colleagues and he could have become an scholar, he chose a way of life that nowadays, we would have called bohemian. He made his first journey to Italy in 1824 and the second one in 1826.

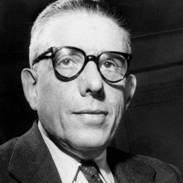

Then, what is known as the "Platen affair" took place. In 1827, Heinrich Heine published the second part of his Reisebilder, which included epigrams of his friend Karl Immermann; one of them made fun of the fashionable orientalism. Immermann didn't refer to any particular poet and I would say that the satire wasn't that bad, but Platen, rather surprisingly I would say, took it personally. His response arrived in another satirical work, Der romantische Oedipus, which included a character that reminded of Immermann, who, in turn, took it rather sportingly. But Platen went even further and attacked Heine with personal allusions; he picked on what hurt the most: he being a Jew. Heine turned on Platen at the third part of Reisebilder, also attacking him in his weakest point: his homosexuality.

They both used their skill with words to hurt each other, and no doubt they made it. They gave a sad spectacle and both came out of it very badly. It was already known in well-informed circles that Heine was a Jew and Platen was homosexual, but one thing was the code "don't ask, don't tell" and another much different having that information being spread in such a rage. Platen, since we're talking of him today, couldn't go back to Germany where homosexuality was considered a crime; He remained in Italy and died of cholera in 1835. His work was overshadowed by the scandal (maybe that's the reason for his limited presence in Lied) until the first years of the 20th century when some people turned their attention to him. Among them, Thomas Mann; It seems that Gustav Aschenbach, from Death in Venice, has much in common with Platen, beyond the evolution of his name from August to Gustav and the resemblance of the surname to his hometown, Ansbach.

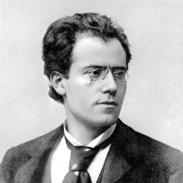

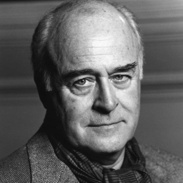

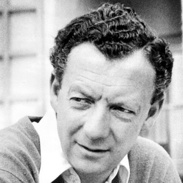

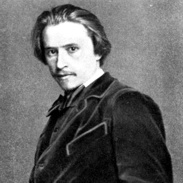

His desperate poems that today we know musicalized, respond to the frustration he felt for his love failures with heterosexual men, sporadic encounters often for money or his difficulty in maintaining a loving relationship; His diary describes in detail his complex and unsatisfying love life. Brahms took the poems of his five songs from Romanzen und Jugendlieder, published in 1820. Along with four other poems by Daumer, these lieder form the Lieder und Gesänge, op. 32, published in 1864, when the composer was thirty-one. They were the first he published after seven years, when he had already published Opus 19 (which included a gorgeous song we heard some time ago, An die Äolsharfe). Maybe we can't say that Opus 32 is a cycle, but neither can it be said that they are merely nine songs unrelated to each other; If we read the poems, we can find some common points, such as the voice in the first person addressed to a second person who is not there or doesn't answer. Besides, the order chosen by Brahms allows us to follow an unrequited love story in which the poetic voice, after struggling, accepts its defeat. Despair and bitterness plan on the cycle / no-cycle, from which we’ve heard so far two songs from Daumer: no. 2, Nicht mehr zu dir zu gehen and no. 9, Wie bist du, meine Königin.

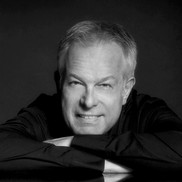

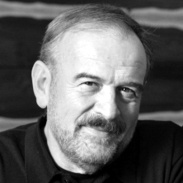

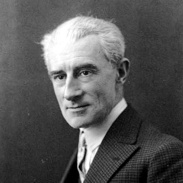

Today, we're listening to the no. 5, Wehe, so willst du mich wieder, a dark and tempestuous song, the only fast in the collection, which seems to open doors to a certain relief. It is a pure strophic song, where the verses of each stanza are divided between an impetuous vocal line (the first four verses) and a windy melody (the last two), while the piano, complex, with character, keeps us in the fight. After the second verse, when suffering soul seems ready to get rid of his enemy, the song is ended by a dark postlude, the right hand following the left in its descent path. I propose to listen to Wehe, so willst du mich wieder, a brausendes Lied (passionate lied) as the poem suggests, performed by Thomas Quasthoff and Justus Zeyen; of course, I like it, but the point is that the recording includes the whole Op. 32. A suggestion in disguise so you might choose to listen to it in full.

Wehe, so willst du mich wieder,

Hemmende Fessel, umfangen?

Auf, und hinaus in die Luft!

Ströme der Seele Verlangen,

Ström' es in brausende Lieder,

Saugend ätherischen Duft!

Strebe dem Wind nur entgegen

Daß er die Wange dir kühle,

Grüße den Himmel mit Lust!

Werden sich bange Gefühle

Im Unermeßlichen regen?

Atme den Feind aus der Brust!

Alas, so you would again,

You hindering shackles, imprison me?

Up and out into the air!

Out streams the longing of the soul,

flowing out in clamorous songs,

Inhaling ethereal fragrances!

Struggle against the wind,

That it might cool your cheeks,

Greet the heavens with joy!

Will timid emotions

Move you as you gaze upon the Infinite?

Exhale the foe from out of your breast!

(translation by Emily Ezust)

Comments powered by CComment