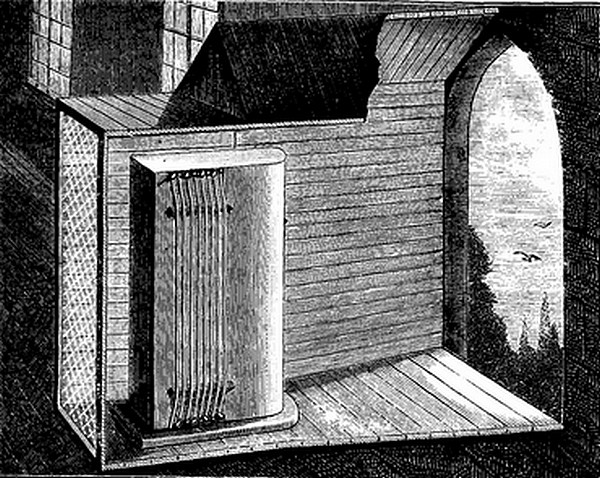

In this context, it's not surprising that the aeolian harp attracted the attention of those romantics. An aeolian harp is basically what its name says: a musical instrument consisting of strings on a bridge near a soundboard. However, no one plays the strings, the wind does it. The air flows and makes the strings vibrate; the soundboard amplifies the vibration and the harp sounds with a timbre depending on the number of strings, their length and thickness, etc. That's to say, as any other string instrument. That invention wasn't new at the beginning of the 19th century; in the late 18th century, when automatons were in fashion, some instruments played by wind were built. The novelty was the interpretation of the aeolian harp: in the 18th, it was considered just a toy, in the 19th, a bond between nature and man, the harp was the sound of nature. Have you ever read Automata, the short story by E.T.A. Hoffmann? I talked about it and also about a song by Schubert some time ago. In that story the characters discuss about the aeolian harp and distinguish between the toy and the instrument that can "penetrate the most sacred secrets of Nature." Automata describes the aeolian harp (in fact, it's a bit confusing, because it names Äolsharfe the mechanical device and Wetterharfe what we know today as aeolian harp) as "thick cords of wire, which were stretched out at considerable distances apart, in the open country, and gave forth great, powerful chords when the wind smote them." We can see that kind of "luxury" harp at the engraving that illustrates this post, a harp at Hohenbaden's castle in Baden Baden. A domestic aeolian harp also existed, with a smaller wooden soundboard; the harp leaned against a wall in the garden or in a window so as the wind made it sound when blowing.

We can find aeolian harps in Hoffmann’s story and also, in poems by Goethe, Kerner, Eichendorff and Mörike, the latter of our interest today. In 1824, when Mörike was nineteen years old and was studying at the seminary in Tubingen, his brother August died at seventeen; some sources speak of "unexpected death", others of suicide. In 1838, Mörike wrote his poem An eine Äolsharfe, where he remembers his dead brother; he asks the wind to travel from the boy’s grave to his garden to play the aeolian harp. The wind brings memories and the harp vibrates in unison with his soul. The poem also contains a very romantic image about aeolian harp: when the wind blew really strongly the harp sounded like human laments coming from the hereafter. However, that strong wind pulls the petals off a rose and that bring the poet back to reality.

Hugo Wolf wrote a beautiful Lied from this poem in 1888 that we heard last month in an post dedicated to the Schubertiade Vilabertran; if you missed, I would suggest to listen to it right now. Wolf wasn't the only composer to be inspired by that Mörike's poem; thirty years before him, Johannes Brahms wrote his An eine Äolsharfe, also a really beautiful song, considered as his first major song. The first stanza is marked as recitative (the same that in Wolf's song); in the second, the composer creates a melancholic vocal line with an etherial accompaniment that leads us to share the yearning and the sadness of the poet. The third stanza begins again with a recitative, but there are just two verses; after that it recovers the melody and the atmosphere of the second one. Our version is by Simon Keenlyside (a way of celebrate his returning to the stage) and Malcolm Martineau. I hope you like it!

Angelehnt an die Efeuwand

Dieser alten Terrasse,

Du, einer luftgebornen Muse

Geheimnisvolles Saitenspiel,

Fang an,

Fange wieder an

Deine melodische Klage!

Ihr kommet, Winde, fern herüber,

Ach! von des Knaben,

Der mir so lieb war,

Frischgrünendem Hügel.

Und Frühlingsblüten unterweges streifend,

Übersättigt mit Wohlgerüchen,

Wie süß bedrängt ihr dies Herz!

Und säuselt her in die Saiten,

Angezogen von wohllautender Wehmut,

Wachsend im Zug meiner Sehnsucht,

Und hinsterbend wieder.

Aber auf einmal,

Wie der Wind heftiger herstösst,

Ein holder Schrei der Harfe

Wiederholt, mir zu süssem Erschrecken,

Meiner Seele plötzliche Regung;

Und hier—die volle Rose streut, geschüttelt,

All ihre Blätter vor meine Füße!

Leaning up against the ivy-covered wall

Of this old terrace,

You, an air-borne muse,

A lute melody full of mystery,

Begin,

Begin again,

Your melodious lament!

You come, winds, from far away,

Ah! from the boy

Who was so dear to me,

From his hill so freshly green.

On your way, streaking over spring blossoms

Saturated with sweet scents,

How sweetly, how sweetly you besiege my heart!

You rustle the strings here,

Drawn by harmonious melancholy,

Growing louder in the pull of my longing,

And then dying down again.

But all at once,

The wind blows violently

And a lovely cry of the harp

Echoes, to my sweet terror,

The sudden stirring of my soul,

And here, the ample rose shakes and strews

All its petals at my feet!

(translation by Emily Ezust)