Verdun, the Ardennes, the Marne, the Somme, Ypres, Gallipoli. Four years. Seventy million soldiers, eight million casualties, two million went missing, twenty million injured. Minefields. Hundreds of miles of trenches in a sea of mud. Next Sunday we will commemorate the centenary of the end of a war that bled Europe.

Guillaume Apollinaire wanted to join the army as soon as the war broke out, but he wasn't admitted because he wasn't French (he was born in Rome of Polish descent). He didn't give up and commenced proceedings to obtain his French nationality; Finally, in April 1915 he went to the front line. A year later he suffered a shrapnel wound in his temple; Seriously injured, he was transferred to a hospital in Paris. At this time, he was granted French nationality. He didn't manage to recover completely from his injuries and in May 1917, he was declared unfit for battlefield service but continued serving in Paris. There, he died at 38 due to the flu pandemic that swept Europe, just two days before the armistice. He didn't stop writing poetry during the whole war and in 1918, he published the volume Calligrames, most of his poems of those years. However, the one I bring today wasn't published until 1925, in the collection Il y a. I'm talking of Bleuet, the tender nickname the soldiers were given.

French soldiers who fought in the WWI were the first (and last) to wear a new uniform. A few years earlier, those thinking heads in the French army had realized that their colourful uniform with red kepi, blue greatcoat and red trousers wore a problem: precisely, that it was too colourful, that's to say, very visible. It was necessary to find a new one to replace it: it had to be less visible, identifiable as French, fully manufactured in France at low cost. When the Great War started, they had to decide in a hurry what the new uniform was going to be and they chose the gray-blue that we've seen in so many movies; someone said it was the colour of the horizon and it was called blue horizon.

At the beginning of the war, the oldest soldiers still wore the previous uniform because the production wasn't able to meet the army's need; they began to call bleuets the young soldiers who arrived at the trenches with their new brand blue horizon uniform. Bleuets, like the blue flowers that we can see in the fields, especially in cornfields, known in English as cornflowers. The flower was linked to the soldiers and became the symbol that remembers the fallen in that war, as in England does the poppy.

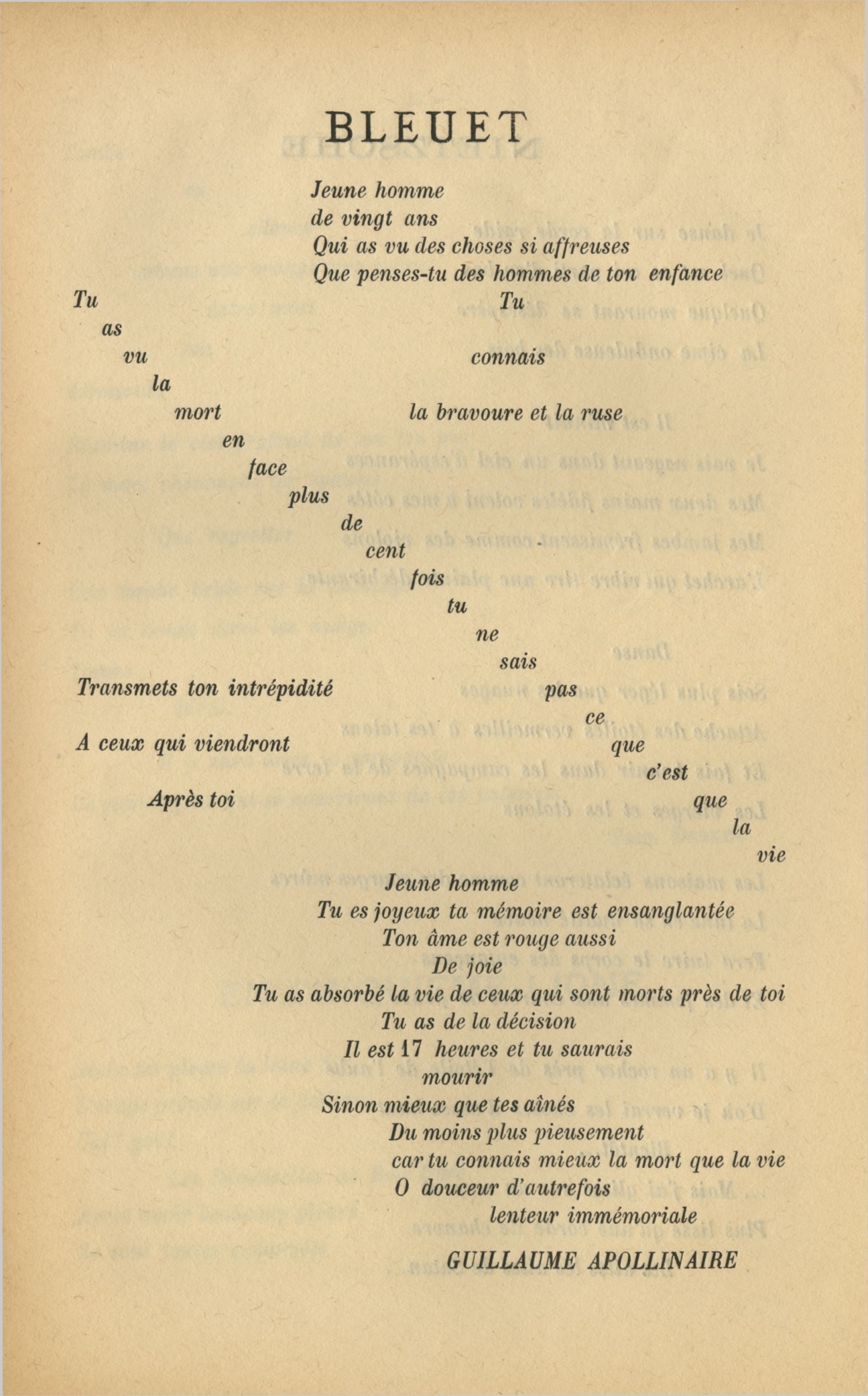

Apollinaire's poem is addressed to a young man in his twenties who will die a few minutes later, at five in the afternoon, when he is ordered to leave the trenches. As always, I'm providing the poem and a translation, but I'm adding here the calligram, as published in the first edition. A sentence, made of monosyllables, goes across the page, like a wound: "Tu as vu la mort en face plus de cent fois tu ne sais pas ce que c'est la vie" [You have seen death face to face over a hundred times you do not know what life is].

The impression that the poem makes is well explained by Francis Poulenc: "Simply moved to my inmost self by the so human resonance of Apollinaire's poem." Poulenc was also a bleuet; a jeune homme de vingt ans that survived the war. He was mobilized in January 1918, when he had just turned 19, and remained at the battle front until the end of the war; then he was on active service in Paris until he joined the army reserve in 1921. We can see him at the portrait that heads this post, painted by his friend Jacques-Émile Blanche in 1920, wearing the blue horizon uniform.

The composer wrote his song Bleuet in October 1939. After only twenty years, Europe was in war again. We can't even imagine how awful that should have been, for all those who had experienced the Great War. I won't tell you anything else about the song, just listen to it, performed by Anthony Rolfe-Johnson and Graham Johnson; the last words of the post are again from Poulenc: "Humility, whether it concerns prayer or the sacrifice of a life is what touches me most ."

Jeune homme

De vingt ans

Qui as vu des choses si affreuses

Que penses-tu des hommes de ton enfance

Tu connais la bravoure et la ruse

Tu as vu la mort en face plus de cent fois

Tu ne sais pas ce que c’est que la vie

Transmets ton intrépidité

À ceux qui viendront

Après toi

Jeune homme

Tu es joyeux ta mémoire est ensanglantée

Ton âme est rouge aussi

De joie

Tu as absorbé la vie de ceux qui sont morts près de toi

Tu as de la décision

Il est 17 heures et tu saurais

Mourir

Sinon mieux que tes aînés

Du moins plus pieusement

Car tu connais mieux la mort que la vie

Ô douceur d’autrefois

Lenteur immémoriale