We all have in mind what the nineteenth century lunatic asylums were like thanks to cinema (and literature), it won't be hard for us to understand Hugo Wolf's horror and suffering when he was locked up. He arrived at Dr. Svetlin's private mental sanatorium on 19 September 1897. He was deceived; his friends made him believe they were going to the Emperor's residence to sign his contract as intendant of the Vienna Opera, because the previous days he had proclaimed that he was the new intendant. He was holding his position with threats and violence, even the most intimate people were unable to control him.

The origin of this episode was a disagreement, probably a misunderstanding, with the real intendant of the Vienna Opera, Gustav Mahler, since four months ago. Wolf hoped that his former conservatory partner, with modern ideas, would premiere his opera Der Corregidor in the city. While Mahler intended to do so in the following season, Wolf demanded that the opera be represented that autumn. The triggering factor was irrelevant, any upset could have caused the crisis. Wolf was entering the third phase of syphilis, which affected the nervous system; an ophthalmologist had detected a few months earlier, on a routine visit, what might be the first symptoms of progressive paralysis.

Wolf forgot that he was the intendant of the Opera in the sanatorium, but he thought to be other characters, as painful as absurds. His state improved after two months of isolation and he was allowed a certain normality. He was able to receive visitors and have correspondence, and even wrote some music: he reworked some parts of the symphonic poem Penthesilea, orchestrated two lieder from the Spanisches Liederbuch (Wer sein holdes Lieb verloren and Wenn du zu den Blumen geht) and arranged for choir and orchestra the lied Morgenstimmung, with poem by Reinick, which he had written a few months earlier.

On 24 January 1898, he was discharged and left the sanatorium. He was not quite sure what he wanted to do with his life, but it was clear to him that he wanted to leave Austria forever, "that country that allowed its children to be locked up in a lunatic asylum". He spent a few days with Melanie Köchert, one of the friends that more often had visited him during the last months (accompanied by her daughter Ilse) and then left with his sister Käthe and Mélanie for a trip to Italy. They arrived in Trieste, where he saw the sea for the first time (I mention it because that made him happy) and boarded on a journey through the Adriatic, which lasted less than they had anticipated because the composer was exhausted.

After visiting his mother and sister Modesta in Windischgraz and Graz, the Köchert prepared a home for him to stay in Vienna. Despite the love that family and friends gave him, he became increasingly depressed. At some point during those months, he wrote to a friend: “I believe it is all over with me. I do not read, do not make music, do not think ; in a word, I vegetate. This is a true picture of my inner being.” One evening in autumn, during a stay in Traumkirchen, they were alarmed that he was not returning home, and went out to look for him. He was found wandering through the woods, wet from head to toe. He had tried to commit suicide by throwing himself into the Tramsee, but the cold and the instinct of survival had made him swim towards the shore of the lake. He had become so ashamed that he had not dared to return to his home.

It was he who requested admission this time, his only condition was not going back to Dr. Svetlin. The Köchert wanted to take him home to take care of him, but it was eventually decided that he would go to the psychiatric asylum of Lower Austria, in Brünnlfeld, in October 1898. The conditions were slightly better, he was now a first-class patient (there were, therefore, second- or third-class unfortunate patients), thanks to the financial contributions of the Hugo-Wolf-Verein, founded the previous year, those of Wolf's friends, who had already contributed to paying the first sanatorium, and also thanks to a life pension granted by Emperor Franz Joseph and another one granted by the Ministry of Culture.

In his room, Wolf had a piano, where he used to perform his Lieder and works by Beethoven and Bruckner. A worker at the asylum (and I would like to mention his name because he brought some light on the sad days, August Stiglbauer) turned out to be a musician who admired Wolf's work, and they often played four-handed. His friends continued to visit him, and he was occasionally allowed to leave the sanatorium; then he pay visits to his friends. But his illness progressed steadily and if he was, for example, in his beloved Perchtoldsdorf, nothing was as he remembered, and he even forgot about himself ("Ah, I wish I were Hugo Wolf!"). He suffered greatly; in a letter written in July 1899 he asked his sister Matilda to “save him, if he could still be saved”; he then tried to escape. In another letter written at the end of that year, he spoke of his situation: scared, misunderstood, with a future that he did not even dare to think about. He ended up by saying: “God of Heaven forgive me if I ever consciously sinned against Him.”

At the beginning of 1900, his paralysis worsened, causing him difficulty speaking. In August, it worsened even more, and he had to sleep in a bed closed with a kind of cage so that he wouldn't fall when he had nerve spasms. In early 1902, doctors said he got a few days left to live, but his heart was strong and stubborn. He died of a pulmonary infection on February 22, 1903, after years of suffering. Two days later, the church where the funeral was held was filled with people who came to pay homage to him.

If you're reading this article on the day it's published, it's 120 years since Hugo Wolf's death. I would like to thank him for his music, the great and wonderful work he composed before the disease dragged him into darkness.

I leave you with one of his works performed at the funeral, Ergebung, the fifth of the Sechs geistliche Lieder nach Gedichten von Eichendorff (Six sacred songs from poems by Eichendorff) performed by Das Vokalprojekt, directed by Julian Steiger.

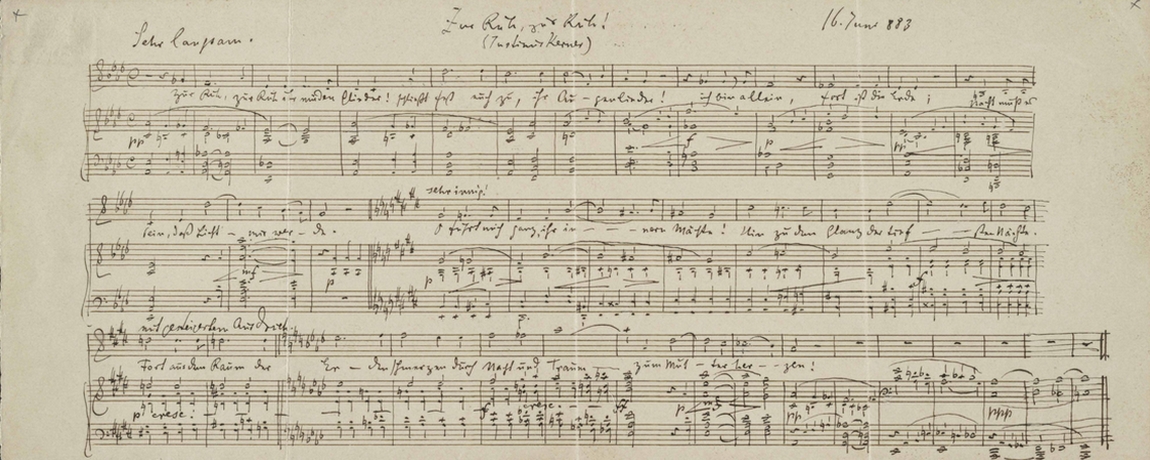

I will also leave you with a few words spoken by his friend Michael Haberlandt at the funeral before he read some verses by Zur Ruh, zur Ruh:

"We thank you for the depth of our hearts for the noble gifts of your art. What you have given to us so royally, we were slow to recognise, and many there are who still do not hear or feel you new, deeply spiritual language, in which you have captured in music the heart and spirit our times"

Verdunkelt schweigt das Land,

Im Zug der Wetter sehe

ich schauernd deine Hand.

O mit uns Sündern gehe

erbarmend ins Gericht!

Ich beug' im tiefsten Wehe

zum Staub mein Angesicht.

Dein Wille, Herr, geschehe!

Please follow this link if you need an English translation