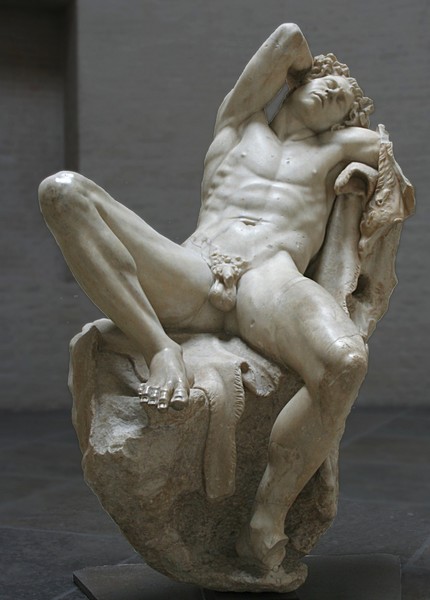

Fauno Barberini

If I ask you the names of Italian composers, it's easy, isn't it? If I ask you Italian composers not known because of their operas... not that easy. And what about Italian song composers? Well, it's becoming increasingly difficult... But we all know Italian song composers! The 19th-century Italian salons weren't unaware of that fashionable entertainment and the most important opera composers (Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini or Verdi) wrote some romanze di salotto, clearly of operatic inspiration, to be performed by amateur singers and pianists with some technical background; Towards the end of the century, the canzone napoletane, originally traditional song, also became parlour songs. Neither a type of song nor the other had artistic aspirations nor, in case they were written from poems, they looked for the relationship between music and poetry that characterizes Lied, so they're not considered Art Song. Some time ago, during our summer holidays, I allowed myself to present a romanza by Paolo Tosti, Vorrei morire, that reliably proofs that we can find wonderful songs in every genre.

In Italy, as in France, England, Russia and so many European countries, the need for an own Art Song also arose, coinciding with a cultural resurgence. The pioneers of this genre, called lirica da camera, are the composers born around 1880, known for this reason as Generazione dell'Otanta. Today, for the first time, we will listen to an Italian Art Song (well, it only took me almost six years!): one of the songs of Deità silvane, a song cycle by Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936). The composers of the Generazione dell'Ottanta developed the new genre according to two tendencies: the most innovative, both in technique and style, represented, for example, by Alfredo Casella, and the most traditionalist, that re-elaborated the inherited musical materials; Respighi worked in this line.

The composer was born in Bologna, in a family of musicians, and he attended the conservatory of his place. To complete his education, he spent som time in Moscow, as the first violinist of an orchestra; during that time he studied composition and orchestration with Rimsky-Korsakov; He also lived for a while in Berlin, working as a pianist at a singing school, to learn about Lied and vocal music. Today he's well known for his symphonic works, for instance the symphonic poems Pini di Roma, Fontane di Roma and Feste Romane, but he also wrote chamber music and very successful operas.

Of course, he also wrote songs, about sixty. He composed Deità silvane in 1917, first for voice and piano and later for an ensemble of eleven instruments. Despite Respighi's influences, we don't hear German echoes in this cycle, but French echoes; At that time of his life, the composer was very interesting in Impressionism and Debussy. Antonio Rubino's poems are also related to symbolism so, all in all, the cycle has a French atmosphere, while still sounds Italian (what kind of Italian Song would be otherwise?).

The beginning of the cycle introduces us in a mythological scene, with fauns and nymphs running around the Garden of the Hesperides (at least, I think so, since we'll find there the nymph Egle). Respighi was fascinated with the rediscovery of ancient Italian music, as a musicologist he recovered many works and wrote from these pieces his three collections of Antiche Arie and Danze, and, by extension, he was also very interested in classical times. Please allow me a digression, taking advantage of our friendship: when I hear about fauns, the images of Fantasia, Beethoven's Sixth Symphony part, come to my mind, I can't avoid it; I don't think a photogram of that film is the best option to illustrate this post, so I chose instead the magnificent Fauno Barberini that welcomes us at the Munich Glyptothek. But maybe some time... Back to Respighi's cycle, the second song, Musica in horto, keeps us in the same cheerful atmosphere; the third one is the dance of Egle; The fourth, Acqua, suggests that something is changing and the last one, Crepuscolo, places us in a decadent garden, where the powerful faun has become a marble statue and the singing fountain is now dry.

We're listening to the first song, I fauni. We hear in the music the fountain, the fauns chasing the nymphs, the nymphs laughing, the flute of the shepherd... A really pastoral scene far from the sad end a few songs later. Our version will be that of Rosa Feola and Iain Burnside.

I fauni

S'odono al monte i saltellanti rivi

Murmureggiare per le forre astruse,

S'odono al bosco gemer cornamuse

Con garrito di pifferi giulivi.

E i fauni in corsa per dumeti e clivi,

Erti le corna sulle fronti ottuse,

Bevono per lor nari camuse

Filtri sottili e zeffiri lascivi.

E, mentre in fondo al gran coro alberato

Piange d'amore per la vita bella

La sampogna dell'arcade pastore,

Contenta e paurosa dell'agguato,

Fugge ogni ninfa più che fiera snella,

Ardendo in bocca come ardente fiore.

Murmureggiare per le forre astruse,

S'odono al bosco gemer cornamuse

Con garrito di pifferi giulivi.

E i fauni in corsa per dumeti e clivi,

Erti le corna sulle fronti ottuse,

Bevono per lor nari camuse

Filtri sottili e zeffiri lascivi.

E, mentre in fondo al gran coro alberato

Piange d'amore per la vita bella

La sampogna dell'arcade pastore,

Contenta e paurosa dell'agguato,

Fugge ogni ninfa più che fiera snella,

Ardendo in bocca come ardente fiore.

One hears in the hills the bubbling brooks

Murmuring through the dark ravines,

One hears in the woods the groan of the bagpipes

With the chirp of merry fifes.

And the fauns racing over hills and through thickets,

Their horns erect above their broad foreheads,

Drink through their blunt, upturned nostrils

Subtle potions and lascivious winds.

And, while beneath the great choir of trees,

They weep, for love of the beautiful life:

The bagpipes of the arcadian shepherd.

Happy and fearful of the impending ambush,

The nymphs flee, faster than wild gazelles,

Their ardent lips like blazing flowers!.

Murmuring through the dark ravines,

One hears in the woods the groan of the bagpipes

With the chirp of merry fifes.

And the fauns racing over hills and through thickets,

Their horns erect above their broad foreheads,

Drink through their blunt, upturned nostrils

Subtle potions and lascivious winds.

And, while beneath the great choir of trees,

They weep, for love of the beautiful life:

The bagpipes of the arcadian shepherd.

Happy and fearful of the impending ambush,

The nymphs flee, faster than wild gazelles,

Their ardent lips like blazing flowers!.

(translation by Emily Ezust)