For centuries in Europe, killing unfaithful wives and their lovers was morally and legally accepted; a man's duty was to protect one of his most valuable properties (his children, not his wife). The most famous case in the music world is that of Carlo Gesualdo, an Italian prince who wrote wonderful music. For us, his crime was murdering two people; for his contemporaries, his fault was not killing them, as he was absolutely entitled to, but humiliating wife and lover noble families by leaving their naked and mutilated bodies on public display.

Although that kind of executions were regarded as a necessary honour redress, there was still some concern: What if a virtuous wife was wrongly killed? Such mistakes caused a sort of collective guilty consciousness which was shown in a number of legends, for instance that of Genevieve of Brabant.

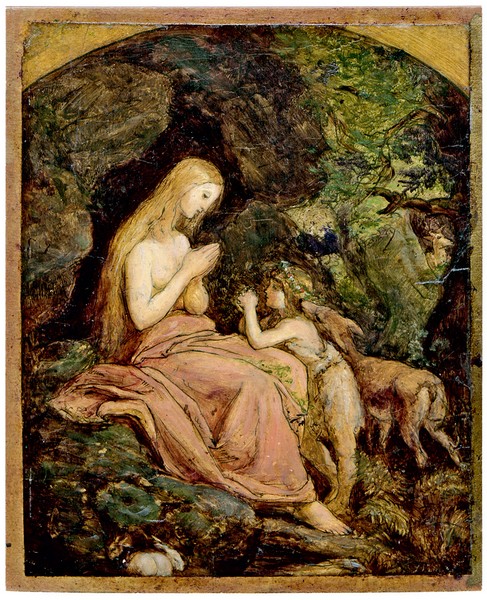

Siegfried of Trier went on Crusades and entrusted his wife, Genevieve of Brabant, to his right-hand man, Golo. Golo fell in love with Genevieve, who rejected him. Bitter and resentful, the man set a trap for the lady and accused her of adultery, reporting to Siegfried: Not only had his wife betrayed him, but she had also given birth to a bastard child (a child who was actually Sigfrid's son). Accordingly, the order Golo was expecting arrived: “Kill them!” Genevieve and the child were taken to the nearby forest to be killed, but the executioners took pity of them and they were abandoned instead. A sort of Snow White, but here there wasn't a cottage and seven dwarfs but a cave and a roe.

Mother and son lived in that cave for six years, fed themselves on the roe’s milk. Until one hunting day, Siegfried chased a roe through the forest until he reached a cave. When he found his wife with her child alive, he tryly believed it was a message from heaven to make him aware of his mistake; needless to say, he deeply regretted it. Genevieve of Brabant never existed, but the cave where she was supposed to have lived became a pilgrimage site and a tradition made her a holy woman; for centuries, she appeared in the calendar of saints' feast days.

Genevieve also inspired many literary works, among them Leben und Tod der heiligen Genoveva (The life and death of Genevieve of Brabant), by Ludwig Tieck, and Genoveva di Brabante by Christian Friedrich Hebbel, that originated the only opera by Robert Schumann, Genoveva. The libretto was by Robert Reinick, and Schumann began to compose it in 1847 and premiered it in 1850. The story is a simplified version, without no child, cave or roe, where the lady saves her life thanks to a supernatural intervention (while the alleged lover is executed without any consideration).

At the beginning of the opera’s second act, Siegfried has just left. Genevieve is alone, anxious because the servants, taking advantage of their master’s absence, have organized a noisy party. Golo comes to her rooms to tell her the good news from the crusades and the woman, happy, asks him to sing for her; this way, she won't hear the servants’ vulgar songs no more. They sing together; Golo can't help telling her his feelings and her misfortune begins.

And what do the two characters sing? A Schumann's Lied, Wenn ich ein Vöglein wär, (If I were a little bird), op. 43/1. You were expecting the story’s song, weren't you?

Genoveva asks Golo to sing "that Alsatian song the troubadour taught them." Therefore, Schumann needed a traditional song. He could have written a new piece for the opera, like so many other composers, but he reused something he had composed a few years earlier, in 1840.

Wenn ich ein Vöglein wär is a traditional song (I don't know if an Alsatian one), collected by Herder in Volkslieder and, a few years later, by Clemens and Brentano in Des Knaben Wunderhorn; In addition, Reichardt collected the tune around 1800. Several versions were written later, including that of Schumann, composed some days after his marriage, a duet that was probably intended for those soirées in his new home. This song was. Wenn ich ein Vöglein wär, published along two more pieces as Drei zweistimmige Lieder, op. 43, is our song this week, performed by Julian Prégardien, Sandrine Piau and Éric Le Sage.

Also, I’d suggest you listen to the song inside the opera, the performance by Ruth Ziesak, Deon van de Walt and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt. It's a long track, we listen at first the original song sang by Genoveva and Golo together; then Genevieve sings alone, as we hear Golo torn apart between his duty and his desire, and, finally, we hear the discussion between the two of them, when Golo tells her about his feelings and she, appalled, rejects him. I wasn't able to find an English translation of the libretto, click here for the German/Spanish version, just in case.

Finally, we have a bonus track. Clara Schumann also wrote a version of Wenn ich ein Vöglein wär, apparently in 1840; a canon that we're listening also sung by Julien Prégardien and Sandrine Piau (just the first stanza)

And after listening to the three versions, get ready, because you'll spend humming the song all day long.

Wenn ich ein Vöglein wär’

Und auch zwei Flüglein hätt’,

Flög’ ich zu dir!

Weil’s aber nicht kann sein,

Bleib’ ich allhier.

Bin ich gleich weit von dir,

Bin ich doch im Schlaf bei dir,

Und red’ mit dir!

Wenn ich erwachen thu

Bin ich allein.

Es vergeht kein’ Stund’ in der Nacht,

Da mein Herze nicht erwacht,

Und an dich gedenkt,

Dass du mir viel tausendmal

Dein Herz geschenkt.

In 1848 and...

In 1848 and...

T...

T...