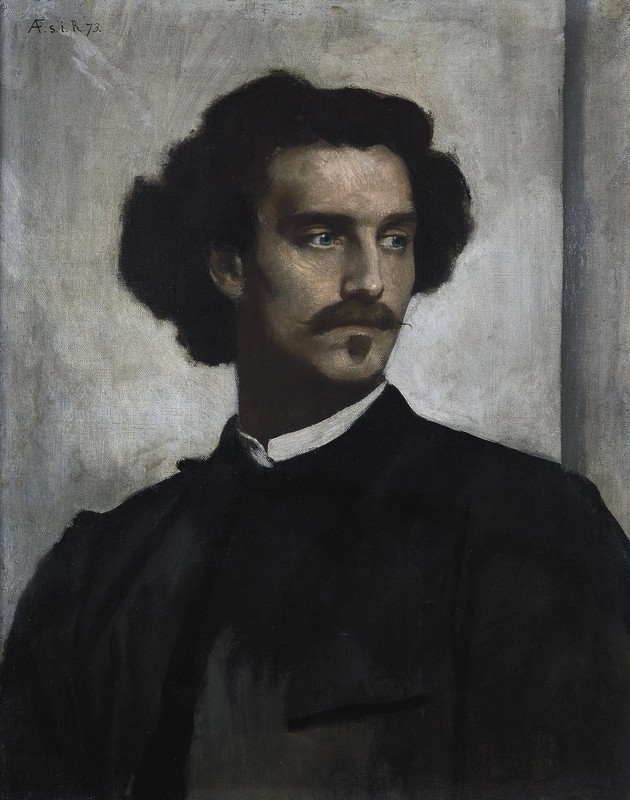

Did you ever walk into a museum room and one piece stood out more than the others? Not a well-known one, nor one you were eager to see, but one you did not know and compelled you to go straight to the other end of the room. It happened to me at the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, with a painting of a man in dark clothes standing on a light gray background and gazing to the left. From a distance, the painting is attractive enough to approach it without noticing the rest for a moment, and then you fall in love with the blue-grey eyes of the man. According to the label, the work is a self-portrait of Anselm Feuerbach, who was for me at that time the author of one of those paintings that I would not tire of looking at, Paeonies (which is not in Berlin, but in Munich).

I later discovered that Feuerbach had been friends with Johannes Brahms. Well, maybe not exactly friends; at least not intimate. They first met in Baden-Baden in 1865; the painter was living in Rome at the time and spent the summer with his mother in the same spa as Brahms, and they met there for some more years. Brahms and Feuerbach had different personalities; the painter was a man of the world, with great personal charm, while the composer was a man with few social skills. In the spa's cosmopolitan (and likely frivolous) ambiance, Brahms must have been somewhat intimidated by Feuerbach's overwhelming presence.

Even though Brahms and Feuerbach didn't have much in common, the composer, who had a keen eye for painting, really connected with Feuerbach's work, which was mirrored in the classics (in his case, the Italian masters). He believed that both sought the same thing in art. He tried to help him get settled in Vienna, and the painter was annoyed. Feuerbach was further upset by a Brahms' remark about one of his works (ah, how tactless could this man be when it came to expressing his opinions!), to the extent that it appears that he destroyed a half-done portrait of him.

The composer did not take it badly, or minimized its significance because when the painter died in 1880, at fifty, he wrote a funeral lament in his memory. He dedicated it to his mother, Henriette, after asking for permission in an affectionate letter.

Feuerbach had painted many works that were inspired by classical Greece (Iphigenia, Medea, The Battle of the Amazons or Plato's Symposium), so it is not surprising that Brahms chose for his tribute a poem with numerous allusions to the Greek world. Friedrich Schiller’s poem, which begins with the words “Auch das Schöne muss sterben” [What is beautiful must also die], is really moving and comforting for those who are grieving. He reminds us that Hades can't be moved by beauty or love; as examples, he talks about Orpheus and Eurydice (the only time the god gave in, even though the story has a sad and predictable ending), Aphrodite and his beloved Adonis, and Thetis and his son Achilles. In the end, however, he contemplates the significance of the tears we shed for our loved ones and demonstrates that being remembered and mourned is a form of immortality.

Brahms wrote a beautiful work with this poem, a work that, I must tell you, is beyond Liederabend's reach; I don't think it has ever been performed in a Lied recital, even with a choir recital. However, you know that at the end of the season, when the temperature is excessively high and many of you enjoy a healthy digital detox, I capitalize on the fact that I am virtually alone to share, shall we say, peripheral works. In this case, I have an excuse, event it's weak, given that Nänie is a song composed upon a poem, and I invoke the beauty of Feuerbach's painting, Brahms' music, and Schiller's words. If you're still here, let yourself be embraced by Nänie, performed by the Radio Choir and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado.

Nicht die eherne Brust rührt es des stygischen Zeus.

Einmal nur erweichte die Liebe den Schattenbeherrscher,

Und an der Schwelle noch, streng, rief er zurück sein Geschenk.

Nicht stillt Aphrodite dem schönen Knaben die Wunde,

Die in den zierlichen Leib grausam der Eber geritzt.

Nicht errettet den göttlichen Held die unsterbliche Mutter,

Wann er, am skäischen Tor fallend, sein Schicksal erfüllt.

Aber sie steigt aus dem Meer mit allen Töchtern des Nereus,

Und die Klage hebt an um den verherrlichten Sohn.

Siehe, da weinen die Götter, es weinen die Göttinnen alle,

Daß das Schöne vergeht, daß das Vollkommene stirbt.

Auch ein Klaglied zu sein im Mund der Geliebten, ist herrlich,

Denn das Gemeine geht klanglos zum Orkus hinab.

does not stir the brazen heart of the stygian Zeus.

Only once did love melt the Lord of Shadows,

and just at the threshhold, he strictly yanked back his gift.

Aphrodite does not heal the beautiful boy's wound,

which the boar ripped cruelly in that delicate body.

Neither does the immortal mother save the divine hero

when, falling at the Scaean Gate, he fulfills his fate.

She ascends from the sea with all the daughters of Nereus,

and lifts up a lament for her glorious son.

Behold! the gods weep; all the goddesses weep,

that the beautiful perish, that perfection dies.

But to be a dirge on the lips of loved ones can be a marvellous thing;

for that which is common goes down to Orcus in silence.

(translation by Emily Ezust)

Comments powered by CComment