We now reach the final part of Tragödie. Last week I mentioned that the poem in the central section, Es fiel ein Rief in der Frühlingsnacht, was not originally by Heine but, as he himself explained, a traditional song. I also told you that in the version of this same song collected by Anton von Zuccalmagio there was a fourth stanza, added to the three included by Heine. It goes like this:

Umschlingen sich zart wie sie im Grab,

Der Reif sie nicht welket, nicht dörret.

embracing as tenderly as they do in the grave,

the frost will not wither them, nor dry them out.

The little blue flowers in the poem could well be the forget-me-nots from the photograph that illustrated the previous article; these flowers (Myosotis is their botanical name) grow all over Europe, bear the same common name in many languages, and are a symbol of faithful love. In the last part of his triptych, Heine takes up the idea of a grave adorned by nature, but in his poem, instead of humble wildflowers, a linden tree rises. For this tree to acquire the imposing yet welcoming appearance it has in Central Europe (from afar, an impressive sight; from up close, its lower branches inviting one to court) many years are needed, which suggests that the lovers of Tragödie lived long ago. That the linden might still be a young tree can be ruled out, since beneath it sits a couple: “the miller’s lad and his beloved” (which takes us to another cycle, doesn’t it?). And this couple, whom we hope will have better fortune in life than the ill-fated protagonists of Tragödie, sense the sadness emanating from the place where they sit, and weep without knowing why. Perhaps the lovers have been forgotten, but there are still those who mourn them.

Of the three parts of the song, this is the one least often performed, because it is a duet, and we know how difficult it is to bring two singers together on stage. Auf ihrem Grab, da steht eine Linde again has a traditional air, but Schumann makes it somewhat more varied and sophisticated. In the first stanza both voices, tenor and soprano, sing together, and both pairs of lines in the quatrain share more or less the same music. In the second stanza, the music departs further from what we have heard so far: the tenor sings the odd-numbered lines alone, and both voices sing the even-numbered ones. The song, and the triptych, closes with a rather long postlude, compared with the overall length of the piece.

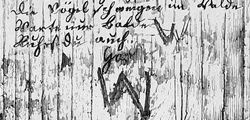

In the first part of this mini-series I mentioned that Tragödie had been Schumann’s first attempt at writing for voice and orchestra, and that he never published it. For many years it was known only from the composer’s diaries, since no trace of the score survived. Until 1991, when it resurfaced publicly: the Heinrich-Heine-Institut in Düsseldorf acquired it at an auction; it was soon edited, and in May 1992 it was premiered in that city. The performers were soprano Inga Fischer, tenor Andreas Fischer, and the Robert-Schumann-Kammerorchester. I do not know if it has been performed again (I hope so), and I am not aware of any recording. Dear readers, if you have further information about the orchestral version of the work, would you share it?

Meanwhile, we will listen to the version for voice and piano, Auf ihrem Grab, da steht eine Linde, performed by Mauro Peter and Nikola Hillebrand, accompanied by Helmut Deutsch.

Auf ihrem Grab, da steht eine Linde,

Drin pfeifen die Vögel und Abendwinde,

Und drunter sitzt, auf dem grünen Platz,

Der Müllersknecht mit seinem Schatz.

Die Winde wehen so lind und so schaurig,

Die Vögelsingen so süß und so traurig:

Die schwatzenden Buhlen,sie werden stumm,

Sie weinen und wissen selbst nicht warum.

Over their grave stands a linden tree,

in which the birds are piping in the evening wind,

and on the grass underneath sits

the miller's boy with his sweetheart.

The wind blows so mildly and eerily,

the birds sing so sweetly and mournfully:

the chattering youngsters, they fall silent;

they weep and they do not know why.

(translation by Emily Ezust)