- Details

This is the last post about the Schubertíada Vilabertran; For different reasons, I'm really looking forward to the three last song recitals so get ready, we have a lot of music to listen.

- Details

The third post about the Schubertíada Vilabertran will be focused on a single recital, that of Matthias Goerne and Alexander Schmalcz on Saturday, August 24. The reason is very simple: we only listened to two of the programmed songs, two songs by Mahler. And since long time ago, I jotted down in my notebook one of the song cycles that Goerne is singing, Sechs Monologe aus "Jedermann", I thought this could be a good opportunity to talk briefly about it.

- Details

During the second week of the Schubertíada, we're listening to the three Schubert's great cycles performed by three different singers who, in addition, have also three different voices: baritone Andrè Schuen will sing Schwanengesang, tenor Christoph Prégardien Die schöne Müllerin and mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, Winterreise. We've listened so far to some songs from the three cycles, so if you want to go over them, that's a lot of (wonderful) work!

- Details

August arrived, it's the time for the Schubertíada. The four weeks of this month will be dedicated to going over eight of the concerts in Vilabertran, paying attention to the songs we listened so far. The ninth concert is that of the Acadèmia and we won't know the programme until a couple of days before so I don't think I can talk about it. As always, I hope these short posts are useful to those of you attending the recitals, and all the readers will have a new song.

- Details

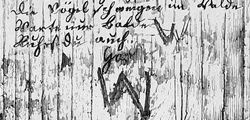

This lied was composed by Franz Schubert in october 1816 for voice and piano. The publication was orderded by Cappy and Diabelli in the 29 may, 1821. Dedicated in “respet” to Johamm Ladislaus von Pyrker, Venice patriarch. The poem was written by Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck and belongs to Op.4, that groups together 3 lieders: Der Wanderer, D.493; Morgenlied, D.685 (poem by Zacharias Werner) and Wandrers Nachtlied I, D.224 (poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)